1 Introduction

Consider a physical process or system which can be described roughly by a finite

set of parameters  and

and  , such as the radiative transfer in the atmosphere and

the optical properties in disjunct layers of the atmosphere confined into the

vectors

, such as the radiative transfer in the atmosphere and

the optical properties in disjunct layers of the atmosphere confined into the

vectors  and

and  . We distinguish between parameters of interest

. We distinguish between parameters of interest  and those

and those  which are required to describe “the rest” of the system. The vector

which are required to describe “the rest” of the system. The vector  is called

state and shall be obtained by measurements. Sometimes there is prior

knowledge about the state. Then an expectation

is called

state and shall be obtained by measurements. Sometimes there is prior

knowledge about the state. Then an expectation  a (’a’ stands for a priori)

and a standard deviation

a (’a’ stands for a priori)

and a standard deviation  a which quantifies the natural variability of

a which quantifies the natural variability of  (climatology) is given. Using an adequate instrument, the outcome of

the measurements will be dominated by the physics of the process. One

writes

(climatology) is given. Using an adequate instrument, the outcome of

the measurements will be dominated by the physics of the process. One

writes

| (1) |

where  is the measurement vector with the measurement values as components

and

is the measurement vector with the measurement values as components

and  is the forward function which symbolises the physics of the process.

In reality

is the forward function which symbolises the physics of the process.

In reality  often also depends on parameters of the instrument but for

the present considerations it is assumed to have a perfect instrument.

Besides

often also depends on parameters of the instrument but for

the present considerations it is assumed to have a perfect instrument.

Besides  , a vector

, a vector  ɛ is obtained, which is the standard deviation of

ɛ is obtained, which is the standard deviation of

.

.

1.1 Forward Model

In order to infer parts of the state from measurements the physics of the process  has to be understood. In detail,

has to be understood. In detail,  in eq. 1 has to be approximated by a forward

model

in eq. 1 has to be approximated by a forward

model  :

:

| (2) |

The forward model should be able to simulate the outcome of the measurement at

least with an accuracy better than the measurement error. In the following, the

dependence of the forward model on the parameters  is ommitted in the notation

and

is ommitted in the notation

and  (

( ) is used instead. But it is emphasized, that knowledge of

) is used instead. But it is emphasized, that knowledge of  is needed to

model the process correctly.

is needed to

model the process correctly.

1.2 Cost Function

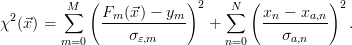

Assume that M measurements have been made and the state to be retrieved has

N components. The cost function χ2( ) is a measure of the deviation of

the simulated measurement from the real measurement and is defined

as

) is a measure of the deviation of

the simulated measurement from the real measurement and is defined

as

| (3) |

To reflect the accuracy of the measurement respectively the prior knowledge each

summand is divided by the corresponding standard deviation σ. The inverse

problem is then a χ2-optimisation problem, i.e. a state  that minimises the cost

function has to be found. If the a priori profile is considered, the resulting state is

the best (optimal) compromise between the a priori knowledge and the

measurement. But as will be seen later in an example the a priori information is

only used where it is needed.

that minimises the cost

function has to be found. If the a priori profile is considered, the resulting state is

the best (optimal) compromise between the a priori knowledge and the

measurement. But as will be seen later in an example the a priori information is

only used where it is needed.

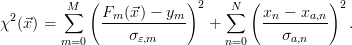

It is expedient to rewrite the cost function in a more compact form:

![χ2(⃗x) = [⃗F(⃗x ) - ⃗y]TS -ɛ1[⃗F(⃗x) - ⃗y] + [⃗x - ⃗xa ]TS -a1[⃗x - ⃗xa].](Inversion28x.png) | (4) |

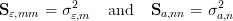

The measurement covariance (M × M) and a priori covariance (N × N)

matrices contain the squares of the standard deviations  ɛ and

ɛ and  a on the

diagonal:

a on the

diagonal:

| (5) |

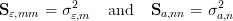

When the off-diagonal elements are filled with zeros than eqs. 3 and 4

are formally equal. There exists a class of inversion methods which fill

the off-diagonal elements with non-zero values in order to get a smooth

result (regularisation). The criterium which  has to fullfill to minimise

the cost function, i.e. to fit the simulated

has to fullfill to minimise

the cost function, i.e. to fit the simulated  (

( ) to the measurement

) to the measurement  is

is

![⃗∇ χ2(ˆx) = 0 i.e. ⃗∇F⃗(⃗x)T S-1[⃗F (⃗x ) - ⃗y] + S- 1[⃗x - ⃗x ] = 0

ɛ a a](Inversion36x.png) | (6) |

Depending on the nature of the relation eq. 1 there are two groups of inversion

schemes: linear one-step and non-linear iterative retrievals.

and

and  , such as the radiative transfer in the atmosphere and

the optical properties in disjunct layers of the atmosphere confined into the

vectors

, such as the radiative transfer in the atmosphere and

the optical properties in disjunct layers of the atmosphere confined into the

vectors  and

and  . We distinguish between parameters of interest

. We distinguish between parameters of interest  and those

and those  which are required to describe “the rest” of the system. The vector

which are required to describe “the rest” of the system. The vector  is called

state and shall be obtained by measurements. Sometimes there is prior

knowledge about the state. Then an expectation

is called

state and shall be obtained by measurements. Sometimes there is prior

knowledge about the state. Then an expectation  a (’a’ stands for a priori)

and a standard deviation

a (’a’ stands for a priori)

and a standard deviation  a which quantifies the natural variability of

a which quantifies the natural variability of  (climatology) is given. Using an adequate instrument, the outcome of

the measurements will be dominated by the physics of the process. One

writes

(climatology) is given. Using an adequate instrument, the outcome of

the measurements will be dominated by the physics of the process. One

writes

is the measurement vector with the measurement values as components

and

is the measurement vector with the measurement values as components

and  is the

is the  often also depends on parameters of the instrument but for

the present considerations it is assumed to have a perfect instrument.

Besides

often also depends on parameters of the instrument but for

the present considerations it is assumed to have a perfect instrument.

Besides  , a vector

, a vector

.

.

has to be understood. In detail,

has to be understood. In detail,  in eq.

in eq.  :

:

is ommitted in the notation

and

is ommitted in the notation

and  (

( ) is used instead. But it is emphasized, that knowledge of

) is used instead. But it is emphasized, that knowledge of  is needed to

model the process correctly.

is needed to

model the process correctly.

) is a measure of the deviation of

the simulated measurement from the real measurement and is defined

as

) is a measure of the deviation of

the simulated measurement from the real measurement and is defined

as

that minimises the cost

function has to be found. If the a priori profile is considered, the resulting state is

the best (

that minimises the cost

function has to be found. If the a priori profile is considered, the resulting state is

the best (![χ2(⃗x) = [⃗F(⃗x ) - ⃗y]TS -ɛ1[⃗F(⃗x) - ⃗y] + [⃗x - ⃗xa ]TS -a1[⃗x - ⃗xa].](Inversion28x.png)

has to fullfill to minimise

the cost function, i.e. to fit the simulated

has to fullfill to minimise

the cost function, i.e. to fit the simulated  (

( ) to the measurement

) to the measurement  is

is

![⃗∇ χ2(ˆx) = 0 i.e. ⃗∇F⃗(⃗x)T S-1[⃗F (⃗x ) - ⃗y] + S- 1[⃗x - ⃗x ] = 0

ɛ a a](Inversion36x.png)